The Place of Women in Literature

The Place of Women in Literature

The female text in literature has long remained an unexplored black continent, a lost point of reference – “Big” (i.e. masculine) prose has ignored it. This is exactly what some literary scholar (in this not-too-distant future, a pro-feminist) will be saying in twenty or thirty years’ time. This problem began to be discussed back in the sixties. By the middle of the twenty-first century, once the errors have been corrected and literature has been replayed, a large segment of the educated male population of the world will join those who talk about it with a pure soul and without the yoke of the past.

Why are women underrepresented in literature?

If we turn to the justifiably aggressive critique of the feminist poststructuralist Helene Siksa, we can realize that the lack of a dense and weighty corpus of women’s texts is really to blame for the “penis-heads. And it is true: throughout human history, repressive phallocratic (as this Frenchwoman would put it) mechanisms have extended not only to family and marital relations – they have also taken a big toll on the space of language.

All systems of governance – in our galaxy, so far represented by men – are fueled by language and at the same time governed by it, which amounts to power and violence (hence the desperate struggle of the new order for feminitives, ridiculous to many).

This is why the figure of the woman in literature embodies the myth of the Echo, the nymph deprived of her own voice, forced again and again by a weak voice to echo the creatures proud of her “pocket symbol. But she is deprived not only of her voice: according to the myth, her body, and with it the very possibility of writing, has been taken from her.

Why writing liberates corporeality

In an important article for poststructuralist philosophy, “The Laughter of the Medusa,” Hélène Siksou loops between academism and poetry and writes that the flesh never lies by exposing itself, by physically materializing thought into text. Women, she argues, must come to know their corporeality through the act of writing. It is a corporeality-text, taken from women by male authors, harnessed to the rusted patterns of the marriage plot with its inevitable domestication: you are an incubator for children – and to have tea by five o’clock (in short, the eternal values of the golden classics).

At this point, Siksu’s programmatic theses remotely echo one of Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari’s interpretations of the “body without organs. It is the concept of an empty shell, alienated from its desires, pleasure and the possibility of verbal or written expression. Postmodernist philosophers constructed this metaphor of a “surgerized,” hysterical corporeality based on the story of André Breton’s “subject,” Nadia, and the writer Henry Miller’s second wife, June.

The cases of these two women are symptomatic of the collective fate of many modernist women. For the patriarchs of literature, “she” is from the strength of an intellectual lightweight, a non-author, a little cardboard doll who can be used only as a framework for the creation of a heroine-often a mutilated and ridiculous dummy of a real prototype. It was this warped perception, the label of hysterical, that June wrote about in a letter to another of Miller’s friends, Anais Nin, lamenting her portrait in her novel, “Tropic of Cancer.” “He wasn’t writing me, he wasn’t writing me… How monstrous it is.” For Breton, a former student studying psychiatry and drooling over young female patients with Louis Aragon, Nadia was something like a laboratory mouse: having probed the material for a potential novel, the surrealist fled.

In the end, we have the truly magnificent stuff of two mastodons of modernism: Tropic of Cancer and Nadia are mast-readers. And in the ’70s, the pus of objectification and unhealthy fetishism in their texts was unearthed and the caricaturedness (if not the stiltedness) of their heroines was exposed. In the end, what Flaubert called the “muse” turned out to be a source of literary vampirism.

Miller did not even try to hide behind a gilded romance: he called the companions that inspired him cunts – and he was not ashamed of that.

To the question of collective destiny: what happened to Nadia or June? June is said to have undergone electroconvulsive therapy and alternately changed her life in motels to a succession of psychiatric wards. Nadia died in 1940 in some hospital is all we know. The second question is: Where are their texts? After all, if we are to believe Kathy Zambreno’s non-fiction study of Heroines, both wrote. There is, however, no evidence that they tried to publish anything. All that remains is an echo, a vague recollection only because men appropriated other men’s registers, preventing them from writing their own story.

What is a woman’s “fear of authorship”

A bible for feminist literary scholars, The Madwoman in the Attic by Sandra Gilbert and Susan Jubar, states that the very possibility of women’s writing was hampered by a lack of antecedents and, as a result, confidence. Based on this construct, Gilbreth/Jubar developed the notion of “fear of authorship,” a malaise fueled by the patriarchal monopoly on art.

Decorative ladies had their pencils knocked out of their hands and were only occasionally allowed to scratch the sheet. No wonder that, without exaggeration, most of the Victorian and Modern women who tried to write ended up in mental institutions. Elaine Showalter’s The Female Malady (a kind of female version of Michel Foucault’s History of Madness) suggests that the girls of the previous century were still lucky: they were at least sometimes allowed to write.

If you turn to the nineteenth century, when woman writing first began to emerge, you immediately stumble over the diagnosis: not only were they not allowed to approach paper at point blank range – this very attraction for women was considered a deviation, a mental disorder.

The archives of hospices and hospitals are full of stories of such “disorders. For example, a Swiss peasant woman was hospitalized in Canton just for delaying work for her morning letter.

In addition to criticizing the vertical of psychiatric power that has served men well, Showalter collects techniques for treating such afflictions: confinement in an attic (hello, Jan Eyre!), pouring cold water (if a bourgeois), but worst of all, no ink.

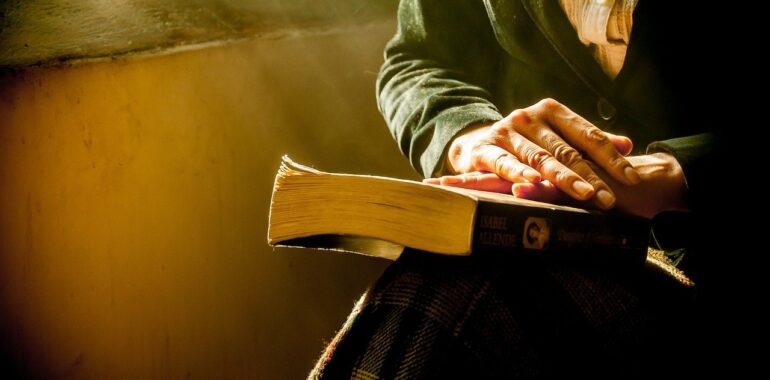

Once an Austrian seamstress, Agnes Richter, imprisoned in the Heilberg asylum, somehow managed to steal some ink. Her ugly jacket is densely covered with illegible text, with occasional dashes of “I want to read,” “I want to write. For feminists, this macabre artifact is further evidence of the repression of masculine language, of the creepy need to wrap oneself in text; for the indifferent, it is a scribble reminiscent of abstractionist Cy Twombly (which is probably fine, too).

Lost Writers

If one makes a pilgrimage to the memorial sites of modernist writers like Jane Bowles or Zelda Fitzgerald, one will run into the voluminous, almost menacing shadow of their author husbands everywhere.

Jane Bowles

An American writer from New York who lived in Tangier, she wrote a novel about the “all-out” journey of two well-to-do ladies.

Playwright Tennessee Williams and Truman Capote called her the most significant novelist of the century – yet her name always goes only in conjunction with that of her husband Paul Bowles.

In Tangier, elbow your way through the hijab-wrapped crowd, and fish out a cab driver. Many of them only need to hear “Po Bo” to know that you want to visit the home of Paul Bowles. Bowles was a great author: admired by beatniks, intellectual trendsetter Gertrude Stein – in short, a bohemian buddy of three whole continents. More importantly, he was the very embodiment of Kipling’s “West is West, East is East,” having lived half his life in Tangier and remained a foreign voyeurist. With his wife Jane, he shared everything but his bed-including the famous house in which they lived above each other and called each other daily, but rarely saw each other.

She was unforgivably little published and translated, and her beautiful somnambulist novel Two Serious Ladies was missed not only by most critics but also by readers. Not a few reviews could do without the phrase “a novel by Paul Bowles’ wife. That’s partly true.

Jane will be angry for the rest of her life that in many ways this is her husband’s novel: constantly edited by him, full of his edits and notes in the margins. In a sense, this man’s weeding out of a woman’s text could be considered a literary monument to gaslighting.

Jane died delirious in a Spanish Catholic convent, leaving behind a half dozen short stories, one play, and a novel. And then there’s the house in Tangier, on which hangs a patina-covered plaque that says, in English and Arabic, “Paul Bowles, American writer and composer, lived here from 1960 to 1999. And no mention of Jane.

Vivienne Heywood Eliot

English novelist, author of a series of short stories.

Her literary legacy was praised by Bertrand Russell, Gore Vidal, and her texts were praised by Virginia Woolf and Ezra Pound. But in searching for Vivien’s creative legacy, you will again stumble upon a figure of men. She is used to being called not a writer, but the “mad muse” of the great poet Thomas Stearns Eliot.

Early in the marriage, the jealous man generously allowed his companion to write. Then she even managed to publish in The Criterion magazine under several pseudonyms, whose lyrical characters had different styles and spheres of interest – just like the famous heteronyms of the poet Fernando Pessoa.

Later, Eliot would write how he hated chick lit (that is, women’s prose) and would not only throw away Vivien’s diaries, but demonize her abilities in front of her friends.

Shards of Vivien’s few surviving notes are preserved, of course, in the Thomas Stearns Eliot Foundation. It’s as if the entire essence of the poet’s relationship to his wife has transmuted into a foundation whose mere name is meant to plunder someone else’s legacy. And what a mystically frightening coincidence that Vivien – like Jane Bowles – spent a fair amount of time in a mental institution.

Zelda Sayre Fitzgerald

American writer, author of the novel and diaries from which Francis Scott Fitzgerald borrowed ideas.

Zelda’s literary value was realized only after her death. She was adored by the New York bohemia of the beginning of the last century, from ballet dancers to art dealers (but hated by Ernest Hemingway). However, not many people knew about Zelda the writer then, for her husband Francis was the slyest of all literary husbands. Giving his doll wife luxurious dresses from Patou and sending her to dances, he meanwhile copied out entire passages from her diaries almost word for word, “screwing” them into his heroines. And, incidentally, still did it in such a way that the confessional, resilient text of Zelda turned into a description of the impenetrable idiots of his novels.

Zelda’s legacy – dozens of voices from novels celebrating one of the most epathetic beauties of the jazz era, novels dedicated to her by her husband Francis Scott Fitzgerald, Tennessee Williams’ play Clothes for a Summer Hotel, Gilles Le Roy’s Song of Alabama, TV series, movies – but where is her own voice?

The sum total of a life – a fire at Highland Hospital, where Zelda was locked in a room awaiting another batch of electroconvulsive therapy, the infernal agony of being engulfed in flames, one novel, letters and diaries stolen by a male writer – and one slipper that miraculously did not burn.

The novel that changed everything (or not)

We owe much of the change in literature to one short story, “The Yellow Wallpaper.” Northeastern United States, late nineteenth century. Longtime Charlotte Perkins Gilman struggles with postpartum psychosis. Around this same period, a still infantile but powerful school of neuropathology, led by Dr. Silas Mitchell, is being erected in the United States. Had the two not met, women might have been weaned from reading and literary craft for a long time and driven into four walls at the first disobedience.

Dr. Mitchell (and society as a whole) believed that it was bad for women – fragile, sickly creatures – to think, so his recommended time for brain stimulation was strictly limited: only two hours a day.

By happy coincidence, Charlotte Gilman’s husband heard about Silas’ miraculous “cure” (regular bed rest 24/7) and brought his wife to the care of a specialist.

Gilman couldn’t last more than three months on this regimen, though. Throwing off the suffocating blanket, she blurted out a short novella about a woman, isolation, and mutating yellow wallpaper. The plot of “Yellow Wallpaper,” at first glance, is simple. Jane suffers after giving birth and, locked in her room by her husband (purely for recreational purposes), spends hours looking at the crazy, wriggling wallpaper. True, there’s a nuance: sometimes a woman’s image shows up in the patterns, and judging by the scratched walls, a madwoman has been held here once before. By the last day of summer, having read all the information from the wallpaper, Jane rips it off and, by some mystical transgression, either goes mad or finds herself – and thus frees herself.

The Wallpaper was said to have been intended precisely for Dr. Mitchell, challenging the suppression of the intellectual, the psychiatric power and the triumph of stereotypes about the mental health of women. It was also said that the novella so shook the neurologist that he fundamentally changed his method of treatment–but this is inaccurate. At any rate, this is what is commonly thought in feminist discourse, which argues that Wallpaper shattered the institution of psychiatry, which was primordially male, and made room for feminist literary studies.

How Feminism Entered Psychiatry

It was easier for the next generation: the American feminist literary criticism of the 1920s and 1930s, intertwined with suffragism, and later the French one of the 1960s, plucked a palimpsest of dusty women’s texts from oblivion: the works of the tandem of Claude Caon and Suzanne Malerbe, obscured by the patriarchs of Dadaism and sura; the religious-philosophical works of Colette Peignot, simply stolen by Georges Bataille and Michel Leiris, or the obscure opuses of Elsa von Freitag-Lorringhofen (the list could go on).

At the same time, psychiatry began to transform: neurophysiology proved that women, contrary to firm prejudice, were no more susceptible to hysteria than men, and intellectual pursuits did not lead women to infertility and insanity.

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders has since been revised five times, and poor Zelda Fitzgerald and James Joyce’s daughter Lucia would today be transformed from schizophrenic women at most into women with a nervous disorder. It is of the thousands of misdiagnoses-not just among women writers-that Showalter shudders, describing how an entire institution of men had a hard time admitting to an inherently wrong course of science and letting female specialists in.

The experimental poet Francis Ponge said that language was a prison for the mind, but whose walls could be painted with anything, even shit. Within this metaphor, it seems doubly appropriate to recall another victim of misdiagnosis. Janet Frame was a New Zealand poetess who painted her poem on the walls of an asylum using sparse pencils, gouache, or simply scratching with her fingernails. She tamed and cleaved masculine language to, contrary to Ponge’s claim, liberate the mind. In 1952, after two hundred (!) sessions of electroconvulsive therapy, miraculously dodging a lobotomy, she left the alabaster vaults of the asylum and published a collection of translucent and at once weighty poetry that tangentially touches on the relationship between art, power and language.

One doesn’t want to overdo the bronze here at all, or stumble over the awkward pathos of the struggle. But Frame, like many like her, shows that writing is the garlands with which a woman wraps her chains, thereby breaking them.